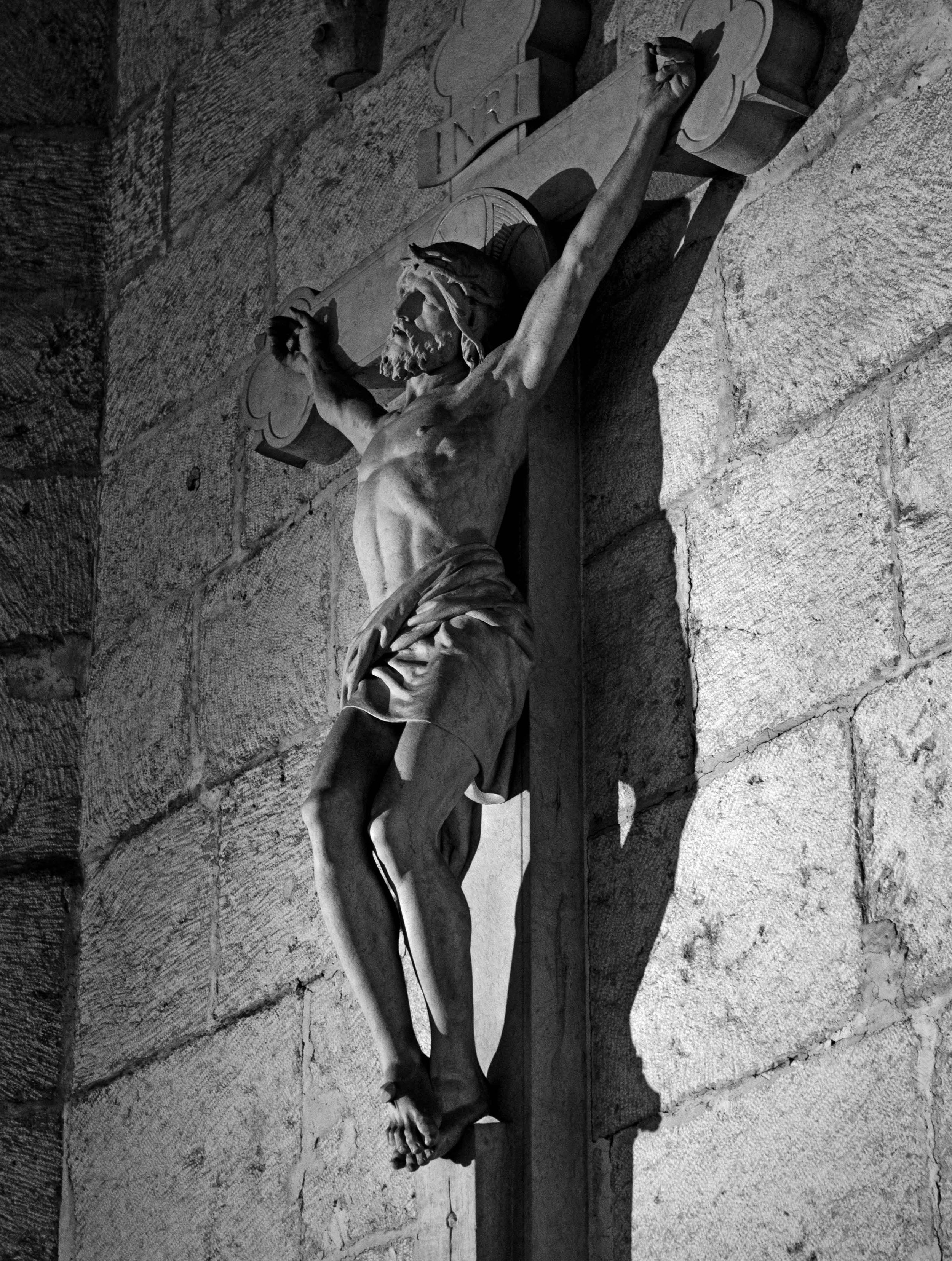

Jerusalem is a heavy place. For much of its roughly 5,000-year-old history it has been a turnstile through which has passed a steady stream of conquerors—with many ownership changes marked by incredible slaughter. In addition, the city is holy to the three Abrahamic faiths—Judaism, Christianity and Islam. Each claims its stake within Jerusalem, and the city plays a central role in end-times apocalyptic visions harbored by all three religions. Jerusalem’s vibe is filled with the weight of its history and the tension of its split religious identities and ethnic divides.

The scene is much different in Tel Aviv, which arose from sand dunes along the Mediterranean Sea in the early 20th century and doesn’t seem to carry as much weight on its shoulders. Surfers trudge along busy city sidewalks carrying boards under their arms as they go to and fro the beach. Rainbow flags hanging from windows and same-sex couple couples holding hands herald its reputation as a gay-friendly city. The European café culture is strong and the city appears thoroughly Western, making it feel apart from the country’s simmering turmoil; that is, until Palestinians in Gaza start launching missiles toward it (which occurred during my time in the country).

Israel, of course, is the Holy Land. It is also the Contested Land, perhaps the planet’s most-conflicted and complicated piece of real estate due to the tussle between Israeli Jews and Palestinian Arabs. During my last full day in Jerusalem I had two encounters that illustrated the seeming intractability of the Israel/Palestine situation, plus another encounter that offered a soupçon of hope.

During an afternoon visit to the ultra-orthodox Jewish neighborhood of Mea Shearim, a man felt compelled to tell me the third Jewish Temple will soon be built on the Temple Mount, the most sacred site in Judaism where the first two Jewish Temples stood (the second was destroyed by the Romans in 70 A.D.). The venerated Western Wall, a prayer and pilgrimage site for Jews, dates from 2,000 years ago and is the western support wall for the Temple Mount. The Dome of the Rock and Al-Aqsa Mosque, together Islam’s third holiest site, have occupied the Temple Mount—the Muslims call it Al-Haram al-Sharif, or the Noble Sanctuary—since around the turn of the 8th century. Some Israeli Jews want to destroy the Dome and Al-Aqsa to clear the way to rebuild the Temple and hasten the arrival of the Messiah. (More likely, it would hasten a horrific war of regional and global implications.) Others say only God should decide when the third Temple will be rebuilt. With that in mind, I asked the man how the third Temple would arise. He replied his rabbi told him Iran would launch a war that would destroy the U.S. and usher in the apocalypse, the third Temple and the arrival of the Messiah. He emphatically stated this scenario would begin unfolding within 11 months (we spoke in November 2019).

That night during dinner at a restaurant in East Jerusalem, I noticed an oval piece of artwork on the wall over my table that depicted the borders of Palestine in a way suggesting modern Israel does not exist. In so many words, I asked my waiter if this represented wishful thinking on the Palestinians’ part. He replied that Palestinian Arabs will soon drive the Jews into the sea. When I mentioned that Israel has superior firepower, he confidently replied that Jews are weak, Palestinians are motivated and victory will be achieved within two years.

Between Mea Shearim and dinner, I sat in on a presentation made by two members of the Parents Circle – Families Forum, a joint Israeli-Palestinian nonprofit organization of 600-plus families who’ve lost an immediate family member during the ongoing conflict. PCFF’s main thrust is that reconciliation is a prerequisite to achieving a sustainable peace. One of the PCFF speakers, a 70-year-old Israeli man, lost his 14-year-old daughter to a suicide bomber. The other speaker, a 26-year-old Palestinian man, lost his 10-year-old sister to an Israeli soldier’s bullet. They shared their stories of grief and anger, followed by their realization that hatred only perpetuates the cycle of violence.

“We are not doomed to repeat this cycle,” said Rami Elhanan, the Israeli man. “Through dialog we can bring down walls.”

PCFF members speak at schools and various public venues to spread the organization’s message. They’ve started a summer camp to bring together Israeli and Palestinian children. “I’m not fooling myself; I know we’re swimming against the tide,” said Elhanan, PCFF’s co-director. He added the aim is to create cracks in the walls they’re trying to bring down. As PCFF says on its website, it’s the only association in the world that doesn’t wish to welcome any new members into its fold. Someday, hopefully, its membership will start decreasing for all of the right reasons.